(Editor’s note: Back in 2002, we marked the first anniversary of the September 11 attacks with an in-depth look at how New York’s broadcasters got back on the air in the aftermath of the worst destruction of broadcast infrastructure in American history. In the years that followed, redesigns of the website caused this report to disappear from easy access. We’re reprinting it today in honor of the 15th anniversary, and in continued memory of the six broadcast engineers and more than 3,000 others lost that terrible day. We’ll follow up on Monday, September 12 with an updated look at how the city’s broadcast infrastructure has evolved in the 14 years since this report was first published here.)

By SCOTT FYBUSH

The transmitter rooms at the top of One World Trade Center were a busy place a year ago this week – as busy, in fact, as they’d been in the quarter-century since New York’s TV stations and several of its FM outlets made the north tower home to their main transmitters, largely supplanting the shorter Empire State Building as the city’s primary TV transmission facility.

The arrival of digital TV to the New York market, and the impending FCC deadline to get DTV construction permits on the air, made for a busy summer up there, 1400 feet above lower Manhattan. In July, WNBC-DT and WABC-DT had been the first of the Trade Center DTVs to sign on, quickly followed by the other digital TV signals that were sharing a new panel antenna on the huge mast that crowned the north tower, WPIX-DT, WNET-DT and WWOR-DT. (The last two Trade Center DTV signals, WPXN-DT and WNJU-DT, had yet to sign on.)

Millions of dollars had been invested in refitting the transmitter rooms to accomodate the additional equipment for the DTV conversion in the nation’s biggest TV market, providing for the extra power and cooling the new transmitters needed.

By that mid-September morning, most of the work had been completed. But there was always someone in most of the big transmitter rooms, even early in the morning, and on that particular day six engineers were settling in for their daily routines in their transmitter rooms: Isaias Riveras and Bob Pattison in the 110th floor space of WCBS-TV (which was analog-only from WTC; its DTV facilities were up at Empire), William Steckman down on 104 at WNBC/WNBC-DT, Donald DiFranco at WABC-TV/DT on 110, Steve Jacobson down the hall at WPIX-TV/DT, and Rod Coppola watching the transmitters of WNET-TV/DT nearby.

They would be among the nearly 3,000 lives lost that morning, at least some of their transmitters running almost to the very end, broadcasting the pictures of their own buildings burning. But by the time the north tower collapsed, with the TV antenna plummeting through clouds of dust to the ground below, the screens of most New York viewers without cable had gone nearly empty.

With the help of some never-before-published FCC documents, this week’s NERW will tell the story of how the New York dial began to return to normal in the days and weeks that followed September 11.

Tuesday, September 11: Panic

The TV broadcasters who used the Trade Center believed they were prepared for just about any eventuality: they all had multiple transmitters and copious sources of backup power at the north tower. The idea that the tower itself would cease to exist was so far-fetched as not to figure in any emergency plans, and as a result only one of the WTC TV stations had an auxiliary facility elsewhere.

WCBS-TV (Channel 2) had put that aux site, its pre-1975 primary location at the Empire State Building, to use once before, when the bombing of the Trade Center basement in 1993 put the transmitters there out of commission for several hours. In 2001, the space at Empire was being used primarily for WCBS-DT (Channel 56), which had beat its competitors on the air by several years as a result of choosing Empire over WTC. A 35 year old Harris analog transmitter still sat there, though, and when the channel 2 signal from WTC finally went dark, WCBS-TV was back on the air in minutes from Empire at more than half its Trade Center power. (Its signal would also be seen nationwide for much of the day on the VH1 cable network, owned by parent company Viacom.)

WCBS-TV (Channel 2) had put that aux site, its pre-1975 primary location at the Empire State Building, to use once before, when the bombing of the Trade Center basement in 1993 put the transmitters there out of commission for several hours. In 2001, the space at Empire was being used primarily for WCBS-DT (Channel 56), which had beat its competitors on the air by several years as a result of choosing Empire over WTC. A 35 year old Harris analog transmitter still sat there, though, and when the channel 2 signal from WTC finally went dark, WCBS-TV was back on the air in minutes from Empire at more than half its Trade Center power. (Its signal would also be seen nationwide for much of the day on the VH1 cable network, owned by parent company Viacom.)

For the other broadcasters who had used the Trade Center, cable (for those viewers in New York City and nearby Cablevision areas whose systems had direct fiber links to the broadcasters) and satellite became the only way to reach viewers at first. Even the remaining New York “superstation,” WPIX (Channel 11), lost its national satellite feed for a few hours; its microwave link to the uplink site had been at WTC.

Within a few hours after the attack, WABC-TV (Channel 7) had begun feeding its signal to several UHF stations with working sites. The school system’s WNYE-TV (Channel 25) and home shopping WHSE (Channel 68), both on Empire, began to carry WABC’s commercial-free programming by early afternoon, joined later on by the New Jersey Network’s WNJN (Channel 50) in Montclair, N.J. (WHSE’s sister station, WHSI in Smithtown, Long Island, on channel 67, also carried ABC programming beginning in mid-afternoon; there were also reports, never confirmed, that Long Island public television station WLIW on channel 21 was carrying some WABC programming.)

The WNBC (Channel 4) signal found its way back on the air, for some viewers at least, via WMBC (Channel 63) in Newton, N.J.; that station also was seen with some programming from Fox’s WNYW (Channel 5).

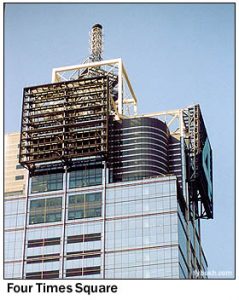

Radio was also knocked out by the attacks: the Trade Center had been home to Columbia University’s WKCR (89.9), Spanish Broadcasting’s WPAT-FM (93.1 Paterson NJ), public radio WNYC-FM (93.9) and Clear Channel’s WKTU (103.5 Lake Success). Only WKTU had a fully-functional auxiliary site, the recently-completed Conde Nast building at Four Times Square; it shifted smoothly from WTC to that site with no downtime.

WKCR and WPAT-FM would remain silent for several days. WNYC lost more than its FM signal; its studio-to-transmitter link to WNYC(AM) also ran through the Trade Center site, leaving no way to get audio from the station’s Municipal Building studios to the otherwise unaffected AM 820 site across the river in Kearny, N.J. To make matters worse, the studios were only a few blocks from the Trade Center, at the top of a tall building that was soon evacuated.

WNYC returned to the air that afternoon from the small NPR studio space in midtown Manhattan; its AM signal was soon restored by sending audio from midtown Manhattan by ISDN to NPR in Washington, where it was uplinked to the NPR satellite. A dish was quickly rushed to New Jersey to receive that signal and get AM 820 back on the air.

Further help for WNYC came that day from WNYE (91.5), the school system’s station in Brooklyn, which quickly agreed to begin carrying WNYC programming, an arrangement that began at noon Wednesday and would stay in place well into 2002.

By day’s end, the TV stations were already making plans to bring a new site on line to restore at least a semblance of on-air service.

Wednesday, September 12: Enter Alpine

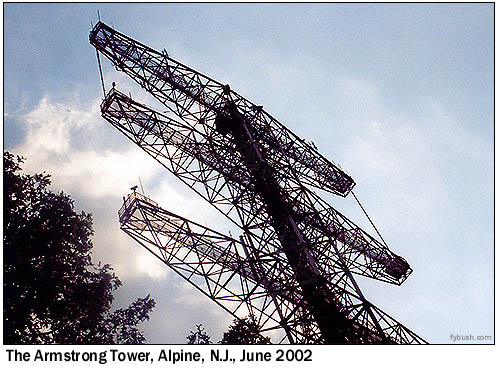

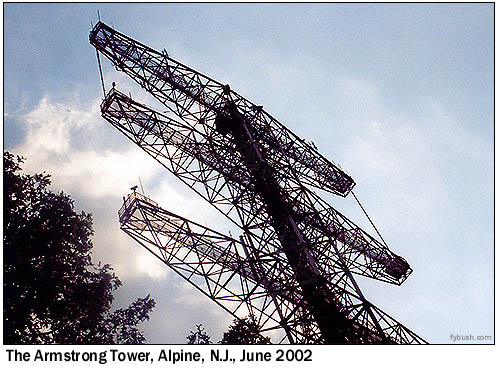

Seventeen miles north of the smoking ruins of the Trade Center, high above the bluffs along the western edge of the Hudson River, the tower built in 1937 by the inventor of FM radio sits as a prominent landmark above the Palisades Interstate Parkway and route 9W.

When Major Edwin Howard Armstrong developed the site for his experimental station W2XMN, it was intended in part as a slap in the face to NBC and its powerful chairman, David Sarnoff, who had encouraged Armstrong to develop FM radio, then withdrawn his support (in favor of TV development) and the use of NBC’s facilities atop the new Empire State Building, a site that was then under the exclusive control of NBC.

At the time, the undeveloped land at Alpine was probably the best alternative to Empire. It was (and is) some of the highest ground in the metropolitan area, with a dramatic view that overlooks lower Westchester County (including Armstrong’s family home directly across the river in Yonkers), the Bronx and northern Manhattan.

At the time, the undeveloped land at Alpine was probably the best alternative to Empire. It was (and is) some of the highest ground in the metropolitan area, with a dramatic view that overlooks lower Westchester County (including Armstrong’s family home directly across the river in Yonkers), the Bronx and northern Manhattan.

On that site, Armstrong built a massive, three-armed tower, rising 400 feet above the Palisades, crowning it with the antenna for his W2XMN. It stayed on the air there until 1954, when Armstrong took his life, deep in depression over a nasty patent battle with Sarnoff’s RCA. The tower never came down, instead finding a new life as a prime perch for communications antennas (and eventually for WFDU-FM at Fairleigh Dickinson University as well.)

And with all that space – and plenty of available power and space for transmitters at the base – Alpine was the immediate choice for an emergency auxiliary site for most of the WTC TV stations. By the end of the day on September 12, Harris and other equipment firms were already diverting low-powered transmitters and antennas intended for other clients to New York, along with engineers to help put them in place at Alpine.

The first station to apply for special temporary authority from Alpine, on September 12, was none other than WNBC – and if the irony of Armstrong’s tower being used to keep the station of his erstwhile rival NBC on the air was noted by anyone at the Peacock Network, it was soon forgotten in the spirit of cooperation that united the city’s broadcasters.

WNBC was back on the air with 2 kilowatts of visual power at 207 meters above average terrain late the next day (Thursday), with equipment on the way as well for WABC, WPIX (granted STA on September 14 with 6.2 kW visual at 244 meters), WNET and one of the two UHF stations that had been on the WTC, Telemundo’s WNJU (Channel 47).

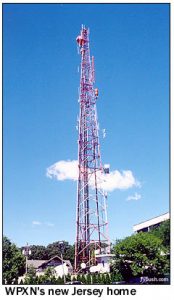

The last of the Trade Center UHFs, Pax’s WPXN (Channel 31), looked in a different direction that day.

The last of the Trade Center UHFs, Pax’s WPXN (Channel 31), looked in a different direction that day.

Across the Hudson in East Orange, N.J., Pax also owned LPTV W23BA, which had recently won permission to change from channel 23 to channel 34. It operated from a tower at 416 Eagle Rock Avenue that had been the original home of channel 68 in its days as WBTB, before it moved to the tip of the Empire State Building.

Before the day was out, Pax filed an emergency STA request to move W23BA to channel 31 and boost its power to 240 kW, becoming in effect an auxiliary WPXN facility (albeit still under the LPTV license).

Pax also had another dormant LPTV, WPXU-LP out in Amityville on Long Island. WPXU had operated on channel 38, but had gone dark when WWOR-DT began its operations on that channel over the summer. (WPXU would subsequently apply to move to channel 19, an application that was dismissed by the FCC this year.)

In a late-morning e-mail to the FCC, which was itself in a state of disarray as a result of the chaos in Washington, Pax asked to be allowed to resume operations on channel 38, saying it believed WWOR-DT “will not resume operation soon.”

The FCC, fast-tracking as much of the recovery process as possible, granted both applications as six-month STAs before the day was out. Covering all the bases, the FCC even assigned a temporary callsign for the channel 31 operation. Did anyone in New York ever know they were watching “W31CK”?

Thursday, September 13 – Saturday, September 15: The FMs Return, Slowly

With much less space needed for their antennas and transmitters, the FM stations that lost their facilities at WTC had a somewhat easier time getting back on the air.

WPAT-FM, silent since Tuesday morning, spent Thursday installing a transmitter at the Empire State Building, feeding the old Alford FM master antenna that rings the 102nd floor observatory. While the Alford had long since been supplanted for primary use by the ERI master antenna higher up the mast (on space vacated by the TV stations’ move to the World Trade Center, ironically), it was still available for auxiliary use by most of the Empire FMs, though even that use was limited by RF exposure concerns for observatory visitors. (The need for a different auxiliary site was what had prompted Clear Channel to build the 4 Times Square site that kept WKTU on the air after the attacks.)

But the Alford still worked, and on Friday WPAT-FM returned to the air with a 719-watt signal from it, on a six-month STA while the station looked for a permanent new home. WNYC-FM also returned from the Alford on Saturday, with an 300-watt mono signal (later boosted to 800) intended as a temporary measure while something higher-powered was being developed.

As for WKCR, it returned to the air on Friday from the Columbia University campus in northern Manhattan, installing one bay of a two-bay ERI antenna on the station’s former STL tower atop Carman Hall, running just 248 watts in mono from 37.2 meters above average terrain. It was a far cry from WKCR’s huge Trade Center signal, but it at least put something on the air at 89.9. (It also restored the radio reading service, In-Touch, that used WKCR’s subcarrier.)

Meanwhile, Empire was also being carefully examined by several of the TV stations that had yet to return to the air, even at low power. Fox had space at Empire for its WNYW-DT, channel 44, and by Friday work was underway to move WNYW’s analog channel 5 facility, as well as recently-purchased sister station WWOR, channel 9, into that space. (WWOR’s signal was also being made available as a subchannel on WNYW-DT for those lucky New Yorkers with DTV receivers; in the meantime, CBS had offered subchannels on WCBS-DT to the city’s other broadcasters.)

WABC-TV returned to the air on Saturday afternoon at 12:50 with a 2 kW signal from Alpine, using a directional antenna aimed south-southeast at Manhattan; installed at space on Alpine that had been intended for its sister station WPLJ (95.5) as an auxiliary facility. WABC’s signal had been dropped from WNYE-TV on Friday night (WNYE would then become a replacement signal for sister public broadcaster WNET); WHSE/WHSI and NJN had also dropped the WABC relay by then.

On Friday, WPIX applied for a 6.2 kW STA signal from the WABC-TV antenna at Alpine – but at the same time, the station had been trying some other ways to get Channel 11 back on the dials of the 30% of New Yorkers without cable. A low-power transmitter was reportedly used from the roof of the Daily News Building at 220 E. 42nd Street, home to WPIX’s studios, on Tuesday and Wednesday; by Thursday, WPIX was running 1 kW visual (with an STA for up to 3 kW) on channel 11 from an antenna on the north side of the Empire State Building at the 81st floor.

(NERW suspects the antenna was aimed out a window of a transmitter room; floors 81 through 85 of Empire are where the transmitters are located.)

That signal didn’t reach south at all, so WPIX went back to the FCC and asked for permission to reactive the long-defunct channel 64 translator that once operated from Empire with 2.5 kW visual. That translator had an interesting history of its own: when the Trade Center went up in the seventies, it was feared that the new signals from its roof would run into multipath problems in Manhattan and the Bronx. In those uncrowded UHF days, most of the VHF stations were granted temporary UHF translators to use to augment their signals – and that’s where channel 64 came from. A verbal STA was granted on Friday to reactivate that southward-facing signal from Empire as well.

WNJU resumed its over-the-air broadcasts on channel 47 on Thursday, using a Scala antenna 117 meters up on the Alpine tower and 10 kW of visual power, leaving WNET and WWOR as the last stations with no over-the-air signal during the weekend.

Week of September 17: Searching for Better Alternatives

The flow of e-mails among stations, engineers, Washington lawyers and the FCC took a breather on Sunday, but resumed in earnest Monday morning as stations tried to improve their weak emergency signals.

At Alpine, it was becoming clear that the site that worked so well for Major Armstrong had some new drawbacks sixty-odd years later. The sheer mass of skyscrapers in lower and midtown Manhattan that had gone up since the thirties served as a wall that prevented the Alpine signals from being seen well, if at all, in Queens, Brooklyn, Staten Island and out on Long Island. Viewers in those areas still found themselves with limited TV choices as the new week dawned, with WCBS still the only truly reliable VHF signal on the dial.

On Monday, WNBC boosted its power from 3.2 kW to 15.9 kW from Alpine, with further authorization the following Friday to go all the way to 52 kW. WABC-TV installed a second, north-facing panel antenna on Alpine for itself and WPIX, intended to send at least some signal up towards Westchester and Rockland counties.

And at WCBS-TV, a retired engineer was brought up from Florida to look after the old Harris transmitter that was keeping channel 2 on the air at full power from Empire. The station procured what was said to be the last amplifier tube for the transmitter in Harris’ stock of parts, and meanwhile made plans to get a new Harris Platinum solid-state transmitter in place at Empire to replace the venerable auxiliary unit that had served it so well.

STAs were granted on Thursday for WNYW-TV and WWOR-TV to resume their operation at low power from Empire; on Friday, WNET became the last of the World Trade Center broadcasters to get a signal back on the air, using a Dielectric panel antenna at Alpine to put 5.91 kW visual on channel 13. It was a weak signal indeed, with significant nulls toward Manhattan and north Jersey (including the actual city of license, Newark), and was upgraded on September 27 to 31.8 kW.

(WNET was aided in early October by the Dish Network satellite service, which offered to add the station’s signal to its package until the broadcast signal could be restored, thus restoring WNET service to many satellite customers in the metropolitan area. WNET also continued to place some of its programming on WNYE-TV, from 6-9 AM and 9 PM – 2 AM, throughout October and November.)

Alpine was also seeing more power from Telemundo’s WNJU, which boosted power to 1338 kW visual from a Dielectric antenna at 83 meters up on the Armstrong tower during the week, under an STA it would continue using until July 2002.

On the radio side, things were getting back to normal a bit faster. On Monday, WPAT-FM moved from the old Alford master antenna (at 1220 feet AAT) to the ERI master, more than a hundred feet higher, still making 719 watts ERP from a 100-watt transmitter.

On the radio side, things were getting back to normal a bit faster. On Monday, WPAT-FM moved from the old Alford master antenna (at 1220 feet AAT) to the ERI master, more than a hundred feet higher, still making 719 watts ERP from a 100-watt transmitter.

WKTU, the best-positioned of the four WTC FMs, kept boosting its power from Four Times Square, going from 8 kW on Sept. 11 to 9.8 kW on Sept. 14, then applying for (and being granted) an STA for 17 kW on Sept. 21. The new signal actually carried beyond the authorized Trade Center signal in some directions, though it remained subject to intermodulation problems from the Empire transmitters in midtown Manhattan. (103.5, under its old calls of WYNY, had moved in 1991 from a directional antenna on the south tower of the Trade Center to the non-directional master antenna on the north tower, shared with WNYC-FM and WPAT-FM. The north tower master was originally intended to accommodate most, if not all, of the FMs then on Empire; with the exception of WNYC-FM and WPAT-FM, none made that move.)

WNYC-FM and WPAT-FM both began looking at Four Times Square as well, attracted by the copious transmitter space and power available, as well as the empty ports on the FM combiner. On September 28, WNYC-FM was authorized for a 13 kW STA from the Times Square tower, with WPAT-FM following suit the next month, applying for and being granted an 8 kW auxiliary facility there. (WPAT’s sister station, WSKQ-FM 97.9, would also apply for an aux facility at Conde Nast in early 2002.)

But perhaps the most unusual e-mail to make its way to the FCC that Monday concerned WNYE-DT, the channel 24 facility licensed to the New York City schools and operating from the old WNYE-TV (and current WNYE-FM) site atop Brooklyn Technical High School. The Federal Emergency Management Agency spent the weekend corresponding with WNYE-DT about using its facilities for something other than broadcast television: replacing its 8-VSB DTV signal with a COFDM data signal.

The idea, quickly endorsed by the FCC in an STA granted Monday morning, was to use WNYE’s digital signal to carry video and audio to recovery workers at Ground Zero, aiding in the limited communications infrastructure at the site. Transmitters and encoders were quickly rushed to WNYE, and a shipment of small receivers was soon on the way from the International Broadcasting Convention in Amsterdam, where they had been on display.

Back to Empire

Even with higher power, Alpine was simply unsuitable for long-term use, at least in its present form. It was too low to “see” above Manhattan and reach the populous boroughs to the south and east and Long Island beyond that. The stations using the tower began working on plans to improve the Armstrong facility for long-term use by late September, beginning with a determination on September 28 by the Federal Aviation Administration that adding 100 feet to the top of the tower would pose no hazard to air navigation.

Even with higher power, Alpine was simply unsuitable for long-term use, at least in its present form. It was too low to “see” above Manhattan and reach the populous boroughs to the south and east and Long Island beyond that. The stations using the tower began working on plans to improve the Armstrong facility for long-term use by late September, beginning with a determination on September 28 by the Federal Aviation Administration that adding 100 feet to the top of the tower would pose no hazard to air navigation.

There was also the neighborhood to take into account, for while Major Armstrong had Alpine all to himself, his tower was surrounded six decades later by “McMansions.” Alpine and neighboring Closter had become some of the toniest communities in north Jersey, with homes almost in sight of the tower’s base fetching well into the seven figures.

The tower may have been there first (and may have been revered as a landmark by radio-history buffs), but the neighbors found it to be simply an eyesore, and it quickly became clear that an extension to Alpine would be difficult to achieve, politically – and would, in any event, be inferior to a midtown Manhattan site. On a practical level, that dictated the Empire State Building, again the tallest structure in New York, but that posed its own set of problems.

First, there was simply a lack of space at Empire. Back when all of the VHF stations had used it, they were the primary tenants, with CBS and NBC each occupying a full floor for their TV and FM transmitters and all seven VHF stations sharing antennas that took up much of the Empire mast. But after the VHF stations headed south to the World Trade Center in the seventies, that space was subdivided, and was soon even more crowded than it had been in the sixties.

Three UHF TV stations (WHSE – later WFUT – channel 68, WXTV channel 41 and WNYE channel 25) occupied considerable space on the rebuilt mast, with more space taken up by WCBS-TV and WCBS-DT, WNYW-DT (soon shared with WNYW-TV and WWOR-TV), and of course the big ERI FM master antenna.

What’s more, the number of FM users at Empire had increased dramatically. While WPAT-FM, WNYC-FM and WPIX-FM (now WQCD on 101.9) had abandoned Empire for the Trade Center, new tenants soon appeared. By September 11, 13 stations shared the ERI master antenna: WXRK 92.3, WQXR-FM 96.3, WSKQ 97.9, WRKS 98.7, WBAI 99.5, WHTZ 100.3 (new to Empire since the TV days), WQCD (which moved back to Empire from the Trade Center in 1991), WNEW 102.7, WAXQ 104.3, WTJM 105.1, WCAA 105.9 (another newcomer), WLTW 106.7 and WBLS 107.5. Three more FM stations, WPLJ on 95.5, WQHT 97.1 and WCBS-FM on 101.1, had their own antennas on the mast.

And some of the space that had been used for antennas in the old days, around and below the 102nd floor observation deck, was no longer suitable for high-power broadcast use because of new radio-frequency radiation concerns.

Add to that the limited facilities for power (Empire has no master auxiliary power supply) and cooling, and the task of putting seven full-power VHF signals, a full-power UHF signal and four more FMs on Empire would be a tough one – and that’s not even taking DTV into account.

Still, it was the place to be, and much of October was spent trying to squeeze every inch of space and kilowatt of power out of the old building. WABC-TV was authorized for 10 kW from Alpine on October 4, but within a few weeks had found a better plan: by using the mast space allocated to co-owned WPLJ-FM, WABC-TV could put up an antenna that it, WPIX and eventually WNET would share. WPIX was granted an STA for 17.4 kW from Empire on October 25, with WABC-TV getting an STA for up to 30 kW from Empire the next day, and both were soon back to Manhattan with adequate signals.

(The move wasn’t perfect: ABC told the FCC that WPLJ, now using the Alford auxiliary master at Empire, was subject to being bumped from that space on two weeks’ notice from building management. A secondary auxiliary antenna on Empire was “partially blocked and of questionable reliability,” while a WPLJ auxiliary site at Alpine had yet to be authorized. Later, WPLJ would diplex into the WQHT antenna on Empire.)

WNBC made its move to Empire in early November, followed on Thanksgiving Day by WNET, leaving WNJU alone at Alpine until the following July 1, when it too would move to Empire. Of the Trade Center TVs, only WPXN remained at a different site, having settled in at the First Mountain site in East Orange with 250 kW visual.

WCBS-TV, too, was eventually relicensed at Empire, with 45 kW visual to make it the most powerful VHF signal in New York.

The FM stations, too, looked to Empire; WKTU filed to make the ERI master antenna its permanent home, an application that was approved just this week. A similar applications from WNYC-FM is pending, and even WKCR says it would like to move to Empire someday. In the meantime, the Columbia station applied in June for a new permanent home at the Riverside Church in upper Manhattan, the erstwhile home of WRVR (106.7, now WLTW). That application, for 6900 watts at 136 meters, is still pending.

Aftermath

The World Trade Center disaster awakened the broadcast community to the reality that even the unthinkable can happen – the tallest building in the biggest city in the nation can simply be wiped off the map in the course of two terrible hours, taking with it most of the market’s television infrastructure.

While analog television in New York was nearly “back to normal” from interim facilities at Empire by Thanksgiving, the city’s broadcasters knew that a long-term solution to accomodate analog and digital TV would require a new tower, at least 1400 feet tall. Since the Trade Center towers were unlikely to be rebuilt at their old height (and indeed, any rebuilding at that site seems years off at the earliest), the broadcasters began exploring the possibility of a new, more limited-use tower at a different site, forming the Metropolitan Television Association to carry out the planning.

Several sites were considered, including Governors Island off the southern tip of Manhattan; problems with short-spacing, air-traffic patterns and with local government approval have focused the MTVA’s attention on possible sites on the New Jersey side, particularly at Liberty State Park in Jersey City or in nearby Bayonne.

Even a broadcast-only tower will still take at least a year, and likely much longer, to get built; in the meantime the DTV dial in New York remains barren, with WCBS-DT and WNYW-DT from Empire as the only full-power signals in Manhattan. Of the broadcasters whose DTV signals had been at the Trade Center, only WNET-DT on channel 61 has returned to the air, at low power from a rooftop near Times Square.

After September 11, broadcasters also realized that the need for an auxiliary site at a separate location was more than just theoretical.

After September 11, broadcasters also realized that the need for an auxiliary site at a separate location was more than just theoretical.

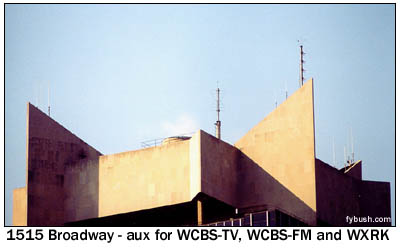

WCBS-TV moved quickly to create a backup to its Empire site, now that the Empire facility was itself the primary transmitter. In the spring of 2002, channel 2 put up a batwing antenna on the roof of 1515 Broadway, the Times Square headquarters of parent company Viacom, to use as a 1 kW backup facility. The 1515 Broadway rooftop had already been home to an auxiliary antenna for Viacom’s WLTW (106.7), later replaced by Infinity’s WCBS-FM (101.1) and WXRK (92.3) after Viacom sold WLTW to Clear Channel and merged with CBS/Infinity. (You can see the batwing in the middle of the photo; the FM aux is on one of the “wings” of the building to the right.)

The Armstrong tower will have an important role to play as an auxiliary site as well; the temporary facilities of WNBC, WABC, WPIX and WNET there are remaining in place for future emergency use. If there ever is a “next time,” New York’s broadcasters will be more prepared for it.

It’s been a long and challenging year for New York’s TV and FM stations, one they hope never to repeat. Someday – someday soon, we hope – all of the city’s signals will again transmit at full power from a new tower site somewhere. When that day comes, we hope the six engineers who gave their lives high atop the World Trade Center that September morning will be appropriately remembered – and we hope due credit will be paid to all of the engineers, vendors, lawyers and FCC staffers who worked so hard last fall to restore broadcast service to New York City.

And speaking of due credit: This NERW Special Report owes much to Michael Ravnitzky of American Lawyer Media, whose Freedom of Information Act request turned up many of the never-revealed details of the FCC’s special temporary authorizations issued in the wake of 9/11. His FOIA request also turned up copies of the special issues that NERW put out last September – which led him to us, and made it possible for us to share this information with you. Thanks, Michael (and thanks to the FCC for reading and filing our reports each week!)