Site of the Week 6/30/2023: On the Edges of Elmira/Corning

Up in the hills and down in the valleys of north central Pennsylvania, checking out some small signals in small towns

by SCOTT FYBUSH

(Originally published November 11, 2011)

It wasn’t hard to decide which site should be the first to be featured here on the new version of Site of the Week: the mighty Blaw-Knox tower at Cincinnati’s WLW (700) was our front-page logo for 11 years at the previous incarnation of fybush.com, it’s still featured on our business cards and pens, and – oh yeah – it’s probably the single most historically significant tower site in the nation.

What’s so special about this one?

It’s one of just two remaining tall Blaw-Knox “diamond” towers from the 1930s. It’s one of the oldest vertical AM radiators still standing. It’s one of the oldest AM sites in the country, period. It’s home to the oldest 50 kW transmitter still in existence, and to the largest collection of 50 kW transmitters at any site in the country. Oh yeah – it’s the only AM station in the country that was ever licensed to run 500 kilowatts of power. (And it’s featured as the “centerfold” spread in the 2012 Tower Site Calendar, too!)

These pictures come from a summer 2010 visit to the site, which has been impressively cleaned up and updated since we first visited in the late 1990s. Today, visitors to the site in Mason, Ohio (some 20 miles north of downtown Cincinnati) are greeted by the sight seen above: no fewer than five 50,000-watt transmitters dating back as far as 1928.

The 1928 transmitter is the one seen at far left: a Western Electric model 7A. By the time it was put into use here on October 4, 1928, the Mason site had already been in service for several years. It was built in 1925 for another station, WSAI, which boasted of its own “super power” (a whopping 5,000 watts) when it constructed the original house-like building and flat-top antenna here.

|

|

Powel Crosley’s WLW had been operating from its own 5,000-watt “high power” facility in Harrison, Ohio, west of Cincinnati, when it settled on Mason as a superior transmitter location – and so Crosley bought WSAI and began building a new transmitter plant next to the existing WSAI facility.

The WLW plant expanded quickly, because Crosley had no intention of stopping at 50,000 watts.

By 1932, he’d applied for experimental 500,000-watt power, and construction crews were busy in the spring of 1933 erecting an addition on the back of the transmitter building, a cooling pond out front, two separate 33 kV power feeds from Cincinnati Gas & Electric – and over in the field to the east of the WSAI building, the mighty 831-foot Blaw-Knox tower, one of the first of its kind, boldly labeled with a giant “W L W” sign across its midsection on the side facing Tylersville Road.

|

|

Let’s head out to the base of that massive tower, still perched (all 200 tons of it!) on its original 1933 insulators and fed by the original 1933-vintage aluminum 10″ transmission line. (72 amps at the base when it was running the full half-megawatt, if you’re curious…)

When we visited last summer, the tower was still supported by its original 1933 guy wires, too, but not for long – last fall, those guys were replaced for the first time in the tower’s history in a nail-biter of a project that had a successful conclusion, thankfully.

The tower is no longer at its original height: like its close cousin a few hundred miles to the south at WSM in Nashville, it proved to be just a little too long, electrically, for its intended frequency, resulting in skywave/groundwave cancellation that impaired nighttime reception of WLW in important communities such as Columbus, Dayton, Louisville, Lexington and Indianapolis.

So the tower’s top section was removed a few years after it was completed, reducing the height to 736 feet. (Much later on, an FM antenna was added to the top of the tower for a former sister station; it’s now Cumulus-owned WFTK 96.5, which operates from a small building of its own behind the WLW transmitter building.)

|

|

Heading back inside the WLW building, we find a veritable museum of AM broadcast transmission over more than eight decades. On the left side, as viewed from the front door, WLW’s oldest transmitters line a wall next to the stairwell that goes down to the ground floor: the 1928 Western Electric 7A at left, and next to it the homebrew Crosley “Cathenode” transmitter that once boasted spectacular high-fidelity performance (and a spectacular low-efficiency power bill to match) before being modified in the 1950s into a more conventional plate-modulated transmitter. To the right of the Crosley, along the rear wall, is a Harris DX50 that powered WLW in the 1990s and into the early part of this century before being replaced by a 3DX50 “Destiny” that sits to the far right of the room, in front of the Continental 317C1 that went into service in 1975.

|

|

But the front room is only a warmup act for the back room. The double doors between the DX50 and the Continental open up into the big back room that’s filled, end to end, by the 500-kilowatt water-cooled monster that bears an RCA badge, though its innards include an RF section built by General Electric and a control system designed by Westinghouse, and its modulator section was the original 1928 Western Electric. (You can read more about the technical history of WLW at Jeff Miller’s excellent History of WLW page.)

To protect adjacent-channel CFRB in Toronto (then on 690), the FCC ordered WLW to directionalize at night; a passive tower was built in a farmer’s field to the northeast to provide some null toward the Canadian signal when Cincinnati was up and running at full bore.

This beast roared its way across the ether for only five years, from its first official sign-on (triggered by a remote control at the White House desk of President Roosevelt) on May 2, 1934 until the FCC declined to renew the superpower authority (under experimental callsign W8XO) at the end of February 1939.

And it remained usable, or so the stories go, well into the 1960s. There are tales – lots of them – of the big transmitter being fired up during World War II to aim propaganda at Europe (though that function was soon filled by another Crosley site just to the east; the “Bethany” shortwave facility that was initially WLW’s international voice quickly became part of the Voice of America, though it was decommissioned in the 1990s and is now a park and museum.)

|

|

While the WLW site isn’t officially open as a museum (and, indeed, still contains a private residence – the old WSAI building next door to the WLW building has been converted into a home that’s been occupied by several generations of WLW engineers), it’s been cleaned up nicely in the last few years and often plays host to visiting engineers, ham radio operators and other interested folks.

The informal tour today includes not only the transmitter floor but also the basement of the building, which is a magnificent piece of history itself. At the bottom of the stairs, a well-equipped workshop allowed many of WLW’s 63 engineers (!) back in the day to fabricate a lot of their own parts. Behind it, a fallout shelter is being rebuilt as a last-ditch emergency studio, and back behind that is perhaps the most awe-inspiring room in the building (which is saying something, considering what’s upstairs): the 40-foot-long vault under the 500 kW transmitter that housed the gargantuan modulation transformers. One was removed (oddly, the one with a blocked path to the outside door!), but the other still sits here, bearing witness to a day when nobody yet knew just how much power would eventually be the maximum for AM broadcasting in the United States.

Thanks to current WLW chief engineer Ted Ryan, his predecessors Paul Jellison and Chris Zerafa, and to Clear Channel’s J.T. Anderton for their insight into the WLW site over the years!

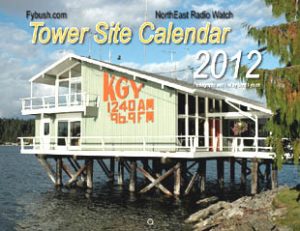

The WLW tower site is one of many you’ll find featured in the Tower Site Calendar 2012, still available from the all new Fybush.com store!

The WLW tower site is one of many you’ll find featured in the Tower Site Calendar 2012, still available from the all new Fybush.com store!

Next week: More Cincinnati, Summer 2010

Up in the hills and down in the valleys of north central Pennsylvania, checking out some small signals in small towns

Getting off the US 15 superhighway to see what's worth seeing around Mansfield, PA

An historic studio building in St. Catharines, Ontario - and an AM that's not there anymore

A quick stop in Richmond for some baseball and radio