Site of the Week 3/28/2025: A Day in Northwest New Jersey

Tower Site goes Jeeping (and fixing a flat tire!) up in the mountains of northwest New Jersey

Text and photos by SCOTT FYBUSH

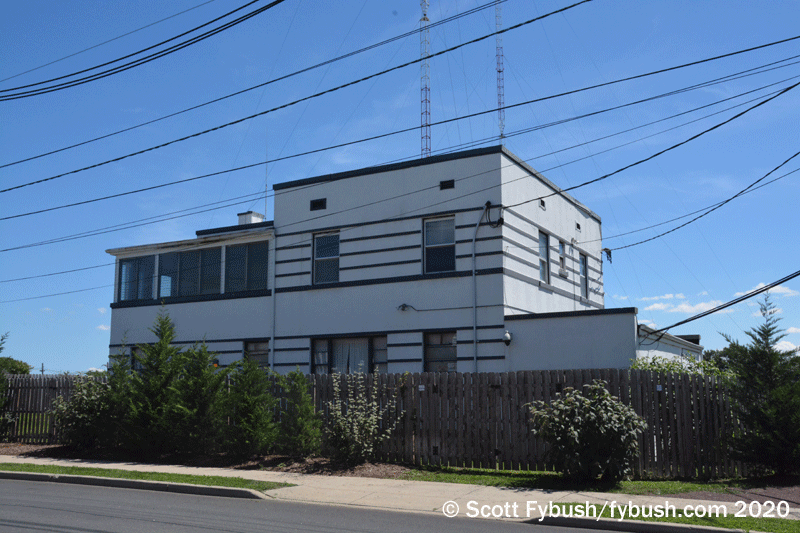

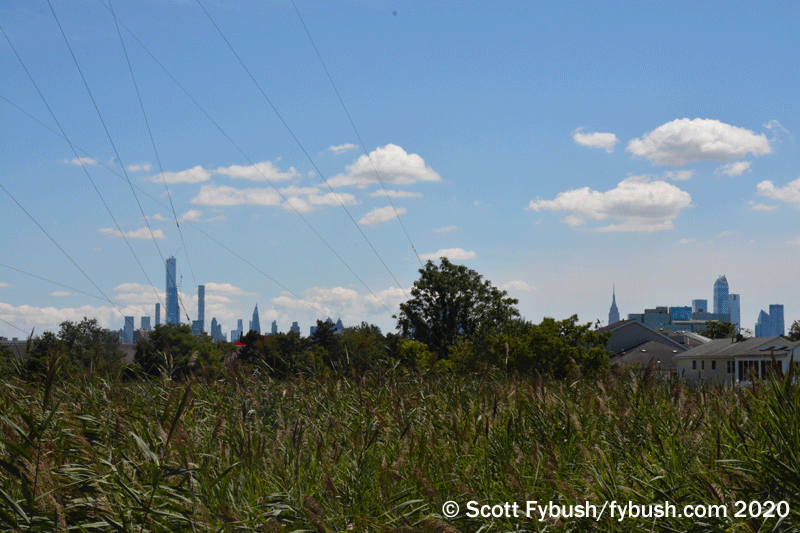

It’s a pretty good bet that whenever you see a place marked “Radio Avenue,” it either had or still has something good on it. In Secaucus, New Jersey, on the other side of the Lincoln Tunnel from Manhattan, it still does – and that something is WWRL, at 1600 on the dial.

WWRL has been out here with its four towers and Art Deco-ish transmitter building since 1951, but its history in New York City goes back 95 years to the summer of 1926, when William Reuman’s Woodside Radio Laboratory put a 100-watt signal on the air from the Woodside neighborhood of Queens. For its first 15 years, WWRL was part of a cacophony of small stations sharing a channel at the top of the dial (1500 kc back then), operating for a few hours at a time before handing 1500 off to one of its share-time partners. That list of mostly-forgotten calls includes WMIL, WMBQ, WLBX, WCLB and eventually just one other station on 1600, WCNW, the ancestor of today’s WLIB.

When the NARBA agreement took effect in 1941, the original plan was for WWRL and WLIB to follow most of the other stations then on 1500 to a new 250-watt “graveyard” frequency, 1490. But in New York, that was problematic, because stations that had been on 1450 generally shifted to 1480, and there was also a New York 1450, WHOM.

The FCC initially planned to move WHOM to 1560 instead of 1480, with WQXR (on 1550 pre-NARBA) going to 1600. Before the shuffles actually happened, though, there was a change: WHOM made the easier move from 1450 to 1480, WQXR got 1560 instead of 1600 – and that left 1600 available for WWRL. (As for WCNW/WLIB? It quickly found a separate home of its own as a daytimer on 1190, leaving 1600 free for WWRL to finally become a fulltime operation.)

With the war intervening, WWRL couldn’t make full use of its potential as a regional signal on 1600 right away. It remained at just 250 watts, non-directional, from its original home in Woodside, Queens for another decade, and it wasn’t until the end of 1951 that it completed its move here to Secaucus and its upgrade to 5000 watts.

By the time WWRL came out here to Radio Road, it was one of the last New York AM stations to move to New Jersey. While its studios stayed in Woodside (and would remain there for another half-century), once 1600 was on the air from New Jersey the only New York AM frequencies then still transmitting from New York City were WNYC (then on 830), WLIB, WEVD and WPOW on 1330 and WQXR on 1560. (And as we showed you a few weeks back, most of those have since moved to New Jersey, while the demise of the longtime 1560 site in Queens marked the end of the last mainland NYC AM site.)

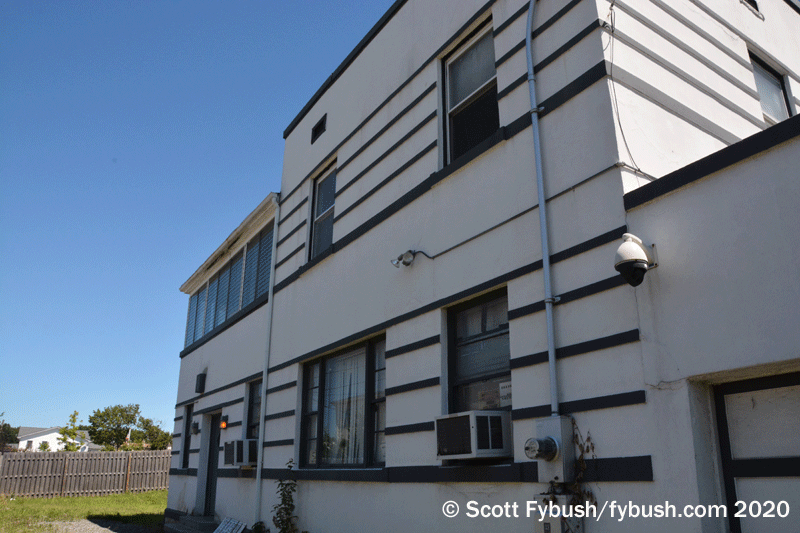

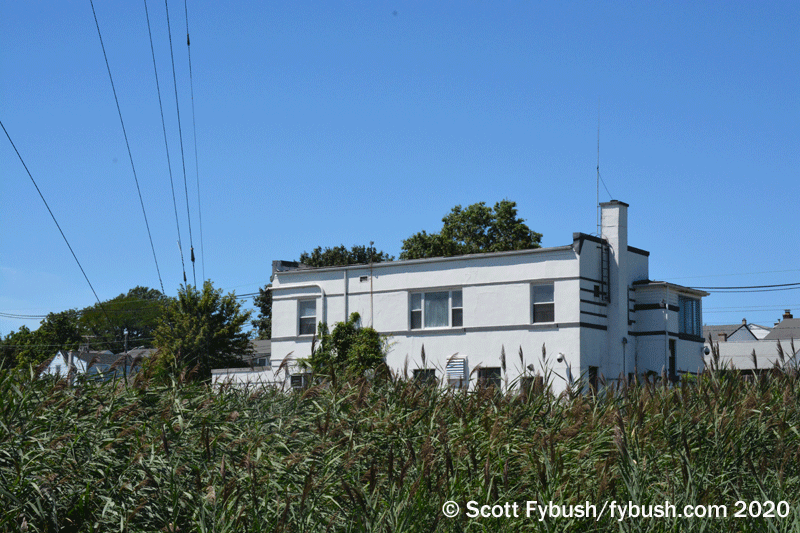

Seventy years later, not too much has changed out here in Secaucus at this two-story building bordering the brackish swamp where the four towers sit.

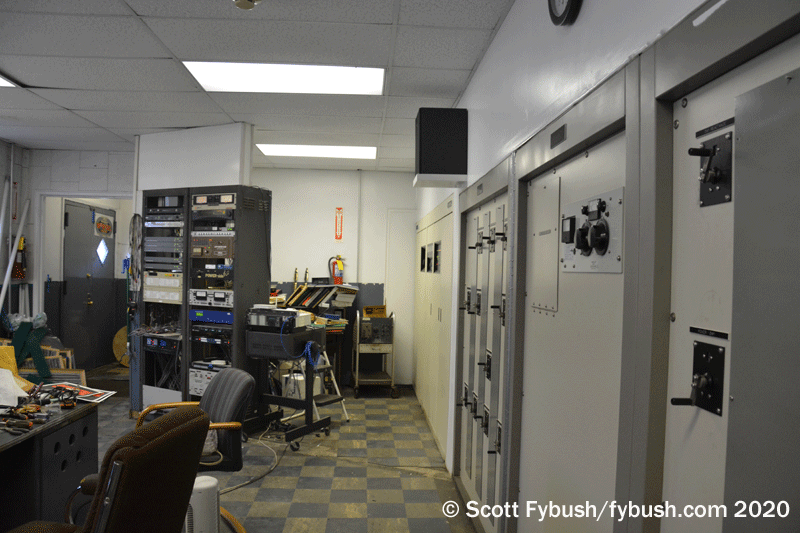

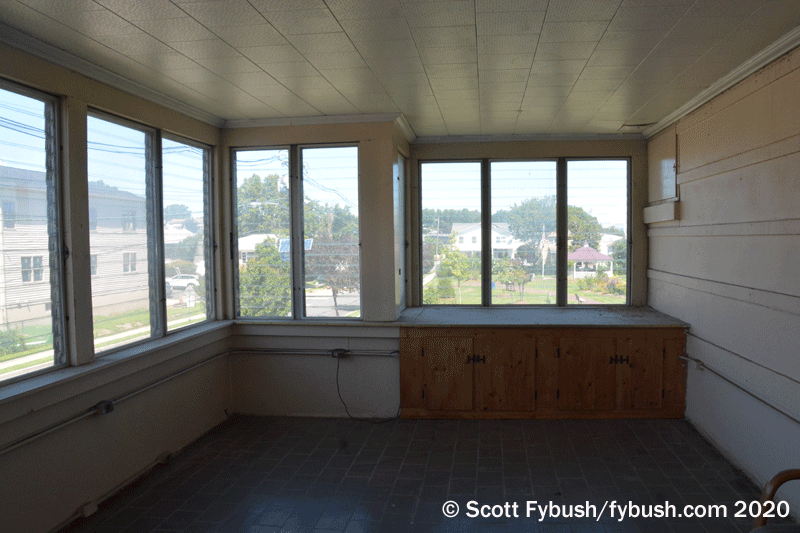

On the first floor of the building, there’s a small space on one side that can be used as an emergency studio (though there have never been regular studio operations out here), a hallway leading to the back of the building, and then on the other side a long main transmitter room.

Over the years, transmitters have come and gone here, especially after a power upgrade a few years back that bumped the 1600 day signal from 5 kW up to 25 kW, requiring the purchase and closure of three other AMs in the region, WERA 1590 in Plainfield NJ to the south, WQQW 1590 in Bridgeport CT to the northeast and WLNG 1600 in Sag Harbor, out on the East End of Long Island. (There was also an attempt back in the 1970s to move the site entirely, shifting it north to Edgewater to better serve Harlem, the focus of the Black-oriented programming that had by then become a WWRL staple.)

By the time we got here in 2020, it was a Harris DX25 powering WWRL’s signal, with much of the rest of the room filled with phasors for the day and night patterns.

By then, some change was afoot here: WWRL was then broadcasting to New York’s Indian community, but with a sale pending to radio giant iHeart, which soon relaunched the 1600 signal as the New York home of its national Black Information Network programming.

(The iHeart purchase also reunited WWRL with its old FM sister: the original WWRL-FM on 105.1 had also operated from the Woodside location, initially with its FM antenna mounted on the old AM tower. The 105.1 signal later became WRFM, moved to the Empire State Building, then went through a flurry of calls, formats and owners before landing with Clear Channel/iHeart as “Power 105,” WWPR.)

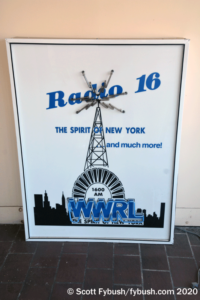

Some traces of WWRL’s earlier formats could still be found upstairs, where there was once an apartment where the station’s engineer could live. Out on the big porch that looks across Radio Avenue, that “Spirit of New York” WWRL sign still has working neon, or so I’m told – and several of the bedrooms are now filled with old remote gear from the days when WWRL was all over the Black community in the city.

WWRL’s history also included some years where it was mainly in Spanish in the 1950s and early 1960s, as well as a few years in the late 2000s and early 10s when it flipped from Black-oriented talk to become the second and last New York flagship for the Air America progressive talk network; in the transmitter room, there are also still signs for the “La Invasora” regional Mexican format that followed the progressive talk in the mid-2010s before the Indian programming arrived.

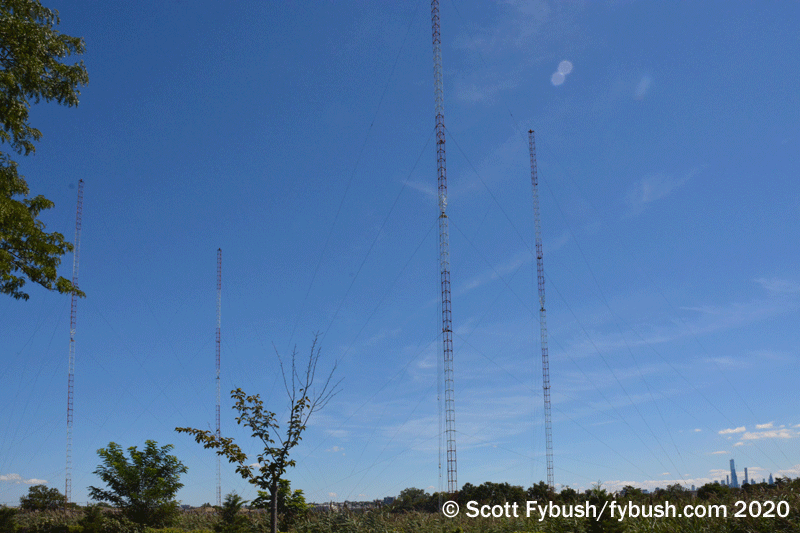

What’s out back here? There’s an old generator in a shed and a series of rickety wooden walkways leading out over the swamp to the four-tower array.

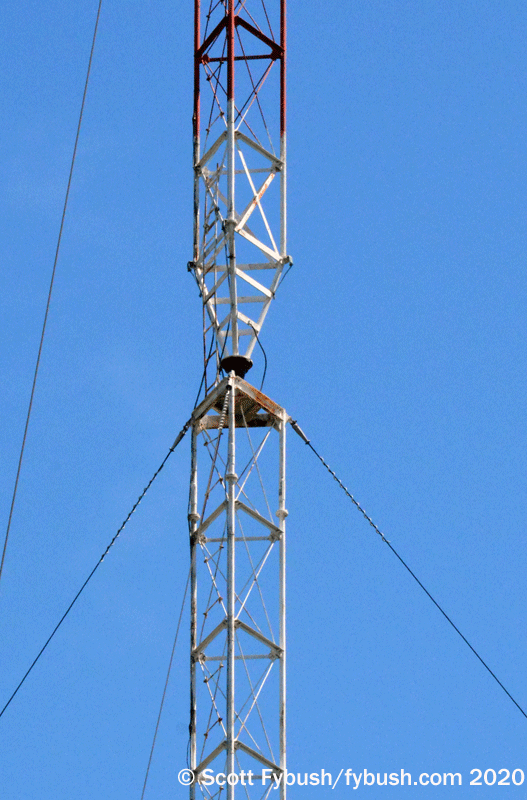

This was an interesting design when it was new. Each of the four towers was segmented, with an insulator and feedpoint about halfway up.

The goal, as I understand it, was to try to better control skywave propagation and focus more of the 1600 signal across the Hudson into the city where WWRL’s target audience was. It never quite seemed to work, and WWRL struggled for years with a deficient signal in much of the city, especially at night. (It was, however, an easy catch at sunrise and sunset up here in Rochester, 300 miles away.)

The antenna system was modified over the years, with the insulators being strapped over and the towers converted to standard series-fed operation. Not long after our visit, an autumn storm ripped through New Jersey, damaging one of these towers and forcing a replacement. (That delayed the switch from Indian programming to BIN by a few months, too, as I recall.)

One more change out here in recent years: along the part of the property that faces the residential neighborhood across Radio Avenue, an earlier WWRL owner had transferred some land to the city of Secaucus, which created a pretty little pocket park that provides some trees, benches and shade for the neighbors.

As this site nears its 70th anniversary, then, we’ll want to get back eventually, both to see the replacement tower and to check out the cleanup and upgrade of the transmitter room.

Thanks to Tom Ray for the tours!

And if you don’t have your Tower Site Calendar, now’s the time!

If you’ve been waiting for the price to come down, it’s now 30 percent off!

This year’s cover is a beauty — the 100,000-watt transmitter of the Voice Of America in Marathon, right in the heart of the Florida Keys. Both the towers and the landscape are gorgeous.

And did you see? Tower Site of the Week is back, featuring this VOA site as it faces an uncertain future.

Other months feature some of our favorite images from years past, including some Canadian stations and several stations celebrating their centennials (buy the calendar to find out which ones!).

We still have a few of our own calendars left – as well as a handful of Radio Historian Calendars – and we are still shipping regularly.

The proceeds from the calendar help sustain the reporting that we do on the broadcast industry here at Fybush Media, so your purchases matter a lot to us here – and if that matters to you, now’s the time to show that support with an order of the Tower Site Calendar. (And we have the Broadcast Historian’s Calendar for 2025, too. Why not order both?)

Visit the Fybush Media Store and place your order now for the new calendar, get a great discount on previous calendars, and check out our selection of books and videos, too!

And don’t miss a big batch of New York IDs next Wednesday, over at our sister site, TopHour.com!

Next week: Rochester’s Pinnacle Hill, updated

Tower Site goes Jeeping (and fixing a flat tire!) up in the mountains of northwest New Jersey

In this week’s issue… New signal for Boston's WJIB - "New Standards" changes stations - New home for Maine FM - Remembering NYC's Diaz, Maine's "Mr. Mike," Albany's McGrath, Rochester's Petschke

A look at two of the Voice of America facilities that were abruptly shuttered this month

In this week’s issue… FCC seeks rule changes - Townsquare, Cumulus close struggling stations - WIRY shuts down - Cumulus spawns "Cat Country" - Toronto's Citytv moves